That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees,

—Those dying generations—at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

(W.B. Yeats, “Sailing To Byzantium”)

One of the great joys of marriage so far has been that of having a companion who consistently spices up my life with his inconsistent schemes, plans, and ideas for new adventures. Whereas I tend to become a little hum-drum and driven by routine, Alex is always coming up with new things to try.

Lately, he’s been working a delivery job most of the day while I’m at home pouring my heart and soul into custom calligraphy projects and new designs for my Etsy shop. It’s a big change from a few months ago when we were at university together, taking most of the same classes and spending the days listening to English lectures together or writing papers side by side.

Thankfully, Alex found a way for us to go on learning together even in this strange transitional stage of our lives. We’ve started listening to audiobooks on Audible and Librivox while he’s doing deliveries and I’m doing calligraphy. So far we’ve knocked out O Pioneers, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Children of Hurin, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Wizard of Oz, The Sword in the Stone, Jane Eyre, Frankenstein, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and No Country For Old Men. It is on this subject that I mean to say a few words, as we’ve been thinking and talking for some time about Cormac McCarthy’s neo-Western noir masterpiece and its Academy Award-winning film.

For me, No Country For Old Men was one of those works that carries its central thematic thread so deep inside that at times the soul of the story seems undiscoverable. Is it a story about fate? The senseless nature of violence? The changing landscape of crime? The far-reaching implications of the drug wars? The new face of the American Southwest? The end of the archetypal cowboy hero?

Or is it much, much bigger than that?

I think we can take a hint from the poem to which McCarthy owes his title: an enigmatic, lyrical piece written by Ireland’s W.B. Yeats and with imagery centered in the ancient Greek city of Byzantium (what is now modern-day Istanbul). This is not cowboy poetry, and what McCarthy has to say is a lot bigger than cowboys. That being said, I think the cowboy is still key.

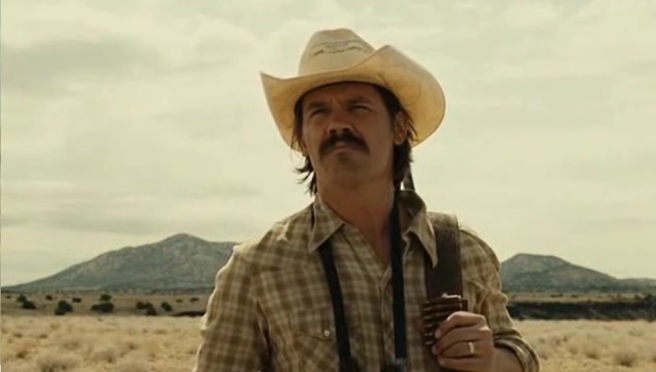

So who are the cowboys in No Country? It’s obvious, of course, that the kindly and old-fashioned Sheriff Bell is one of them. However, although he is much younger than Bell, Llewelyn Moss may be one of the most important cowboys in the story and although it took me awhile to recognize it, I think Moss might be a quintessential “old man,” in the sense of the story’s title.

Moss is a Vietnam vet in his mid-thirties, and a wannabe cowboy hero. He seems to see himself as a sort of crusading bad-ass lone ranger, a John Wayne character in the flesh. Even his name lends credence to this reading: “Llewelyn” is rooted in old Welsh and “moss” is reminiscent of a forest full of history and years. Moss seems convinced that his skills and intelligence, coupled with the justice of his cause, will ultimately triumph. Although he experiences fear and consternation, he is never so overcome by these things as to reach out to law enforcement for help. He thinks he’s a cowboy boss-man: tough, gritty, brave, brusque, resourceful, authoritative, a man of action and command, capable of violence and extreme steps, but just and righteous.

Moss is a Vietnam vet in his mid-thirties, and a wannabe cowboy hero. He seems to see himself as a sort of crusading bad-ass lone ranger, a John Wayne character in the flesh. Even his name lends credence to this reading: “Llewelyn” is rooted in old Welsh and “moss” is reminiscent of a forest full of history and years. Moss seems convinced that his skills and intelligence, coupled with the justice of his cause, will ultimately triumph. Although he experiences fear and consternation, he is never so overcome by these things as to reach out to law enforcement for help. He thinks he’s a cowboy boss-man: tough, gritty, brave, brusque, resourceful, authoritative, a man of action and command, capable of violence and extreme steps, but just and righteous.

[SPOILERS AHEAD]

However, in what I think it is the central element of the story, McCarthy will not allow Llewelyn to be the hero he thinks he is. Llewelyn, he wants us to know, is deluded in thinking he is the hero of the story. On the contrary, his self-sufficient arrogance brings death and sorrow to everyone he encounters, from his wife and her mother to the teenage runaway girl he is mentoring and “protecting” with a cynical, detached air when she is brutally killed along with him in the motel.

In every possible way, McCarthy is undermining and overturning the archetype of the cowboy hero that Llewelyn aspires to be. In what is perhaps one of the most significant story-telling decisions he makes, McCarthy chooses to have Llewelyn killed off-screen. He does not even dignify the cowboy hero with a heroic final stand. Llewelyn thinks he is the hero, but in the end, he is merely insignificant collateral damage in a war much bigger than him, and his stubborn insistence on getting involved in that conflict makes him the agent of destruction to his own family.

So what is the significance of how McCarthy treats Moss’ character? I think the answer lies in his foil: Sheriff Bell. The other “old man.”

While Bell is also a cowboy and an old-fashioned man of action, what sets him apart from Moss is his humility. Unlike Moss, Bell doesn’t see himself as the hero of the story, and he is full of misgivings about his own adequacy for the position he’s placed in and his ability to tackle the challenges posed by the brutal drug wars intensifying in the southwest. In the end, Bell makes responsible choices for himself and his wife, and avoids the pitfalls of bravado and arrogance that prove the ruin of Llewelyn.

So how does all this fit in with Yeats? It’s a question I’ve been puzzling over for weeks now, and I’m still uncertain about which interpretation to pursue, but I have a few thoughts on the subject.

I think it’s very tempting to assume that the Yeats’ tie-in is a reference to the fact that Sheriff Bell sees the new Southwest (and, by extension, perhaps the whole world) as an unfit place for the wise and for those committed to traditional ideals of justice, righteousness and sanity. Just like Yeats, Bell finds himself lost in the morass of modernity. You could even make the argument that Bell sees earth itself as unfit for good men. Unlike Llewelyn, he recognizes that the earth is not a place where the just are necessarily rewarded, not a place where good men always triumph. Perhaps, like Yeats, he is hungry for “the artifice of eternity.”

However, I wonder if this interpretation is not a bit too easy, a bit too surface-level. Also, it hardly suffices to explain Llewelyn’s prominence in the story and the decisions made by both McCarthy and the Coen Brothers to consistently reverse our expectations for his character. To me, Llewelyn’s character prevents us from interpreting the theme of this story as a direct adaptation of Yeats’ idea. Rather, I wonder if we’re being challenged to challenge Yeats’ own take on the old men.

Is there something harmful in self-identifying as part of a wise and righteous minority? Perhaps not necessarily. But I think Llewelyn’s character points to the imminent danger of hubris and destructive arrogance that so often accompanies the determination to be an old-fashioned hero. And, what may be more to the point, he is a living (well, OK, not living anymore) warning against the oh-so easy assumption that we’re always on the right side simply because we understand our own motives and fail to understand the motives of others. Maybe McCarthy is suggesting that there is an inherent danger in Yeats’ own self-congratulatory statement.

Is there something harmful in self-identifying as part of a wise and righteous minority? Perhaps not necessarily. But I think Llewelyn’s character points to the imminent danger of hubris and destructive arrogance that so often accompanies the determination to be an old-fashioned hero. And, what may be more to the point, he is a living (well, OK, not living anymore) warning against the oh-so easy assumption that we’re always on the right side simply because we understand our own motives and fail to understand the motives of others. Maybe McCarthy is suggesting that there is an inherent danger in Yeats’ own self-congratulatory statement.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and opinions. What do you see as the central theme of No Country For Old Men? (the film or the novel) How do you reconcile it with “Sailing To Byzantium”? What do you see as the significance of Bell and Llewelyn’s characters? Is there any country for old men? Who are the old men?